|

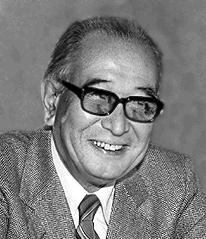

The Director's Heart: Akira Kurosawa,

1910-1998 (Director of "Throne of Blood") : Akira Kurosawa Web Site

"The root of any film project for me is this inner need to say something," he once wrote. Whether a samurai epic or a modern detective story, what he had to say always revolved around the conflicts that thrived in the hearts of his characters: dreams vs. duty; honor vs. self-interest; nobility vs. survival. In each of his 30 films he gave voice to these elemental struggles-the tug-of-war in the soul of life out of which all things flow. With the acclaim that followed the international release of his masterpiece Rashomon in 1951, and The Seven Samurai three years later, Kurosawa became better known in the West than any other Japanese filmmaker. His popularity awakened the rest of the world to Japan's film industry, while eliciting respect and homage for his own work from filmmakers abroad. The Seven Samurai inspired The Magnificent Seven in 1960, while another samurai film, Yohimbo (itself based on Dashiell Hammett's "Red Harvest") was the basis for Sergio Leone's 1964 western, A Fistful of Dollars. While a handful of Japanese critics frowned on Kurosawa's kinship with American westerns and film noir, the director considered the opportunity to link together traditions as culturally distinct as the Japanese Noh play and the American gangster film part of the power and pleasure of making movies.

He was born in 1910, in Tokyo's Omori district, the youngest of eight children. His father, a teacher, took his family to the movies often because-contrary to the opinions of his fellow teachers-he believed they had "educational value." Although the young Kurosawa would later frequent the silent-movie house where his older brother Heigo worked as a benshi, narrating foreign films for audiences, he considered movies little more than a pleasant diversion. His own artistic aspirations were as a painter. Although he failed the entrance exam to art school at 17, he painted on his own and was good enough to have two of his works exhibited. For a while he led a bohemian life, painting and sketching, immersing himself in the writings of Dostoevsky and Gorki (whose works he would later film), and living cheaply with friends whose leftist activities occasionally drew the wrath of the police. Kurosawa's own politics were less dogmatic. He was an artist first-albeit an increasingly frustrated one, unable to break through to what he felt was a strong personal style.

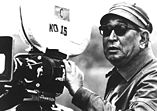

Kurosawa believed the director's role encompassed every aspect of production, from coaching the actors to mixing the sound. While his painter's sensibilities were responsible for the stunning visuals that many regard as his claim to genius, he was also an excellent editor with an intuition for rhythm and timing. (1963's High and Low contains some of his finest work in this area.) On all his productions, he'd do a nightly rough-cut of each day's shooting to give himself, his cast and crew an immediate idea of the direction a film was taking.

"I put the A camera in the most orthodox positions, used the B camera for quick, decisive shots and the C camera as a kind of guerrilla unit." He would continue to make use of this technique for the remainder of his career, even in films where the action level was low, because he found it allowed his cast to be more natural. "With multiple moving cameras," he pointed out, "the actor has no time to figure out which one is shooting him. Kurosawa could be a tough man to work for, storming off projects when things didn't suit him, and having sets torn down if the slightest detail was wrong. He treated his actors gently, yet could demand Promethean efforts of them as well, as during the filming of Throne of Blood (1957), when he insisted that Toshiro Mifune wear a protective vest and be shot with real arrows.

Kurosawa's staff sometimes referred to him as kaze-otoko, or "wind man." The name dates back to his first directorial effort, Sanshiro Sugata. The final sequence, a magnificently staged fight to the death between two martial-arts masters, takes place in a wind-swept field in which the combatants are all but obscured by the tall, swaying grasses that envelop them. The human drama Kurosawa creates by allowing us only a few glimpses of the fighters' flying limbs is enhanced, then ultimately dwarfed, by the overpowering presence of the punishing wind with which they both must contend. In this one scene, barely five minutes of film, Kurosawa shows us that the greatness which would follow over the next half-century-the fluency with visual images, the instinct for knowing whether to make a scene unfold, or explode had already taken root. And it's here that he begins to explore the relationship that would fascinate him for the rest of his career, the one between man and nature. In all of his films, Kurosawa delighted in framing his characters against vast backdrops of sky-not merely for the beauty shot, but to contrast the scope of man's endeavors with the enormity of the world around him. Likewise, it is hard to think of another director who managed to use rain with such success as both a narrative and pictorial device. It provides the veil of uncertainty through which much of Rashomon is told; carries us into the netherworld in the opening segment of Dreams; engulfs the savage necessity of the climactic battle in The Seven Samurai. It's easy to come away from Kurosawa's films with renewed awe for the power and magnitude of nature. If we allow them to show us, in nature's beauty and terror, in its ability to destroy and restore, a perfect reflection of ourselves, then we'll begin to have some understanding of what was in the director's heart all along. Courtesy of the MovieMaker Magazine Website

|

|||

The

essence of a director is more than the sum of his skills; it's in the stories

he chooses to tell. Throughout 50 years of filmmaking, Akira Kurosawa's

reputation as a superior craftsman was never in dispute. It's as evident in

the panoramic sweep of his battle scenes as it is in the poetic grace with

which he could denote the passage of time. But his enthusiasm for the

possibilities of his art went beyond a mastery of technique. Kurosawa, who

died in September of a stroke at the age of 88, saw film as a dynamic and

versatile language with which he could praise the forces of nature, decry the

evils of man, shed light on the problems of his country, and celebrate the

resilience of the spirit.

The

essence of a director is more than the sum of his skills; it's in the stories

he chooses to tell. Throughout 50 years of filmmaking, Akira Kurosawa's

reputation as a superior craftsman was never in dispute. It's as evident in

the panoramic sweep of his battle scenes as it is in the poetic grace with

which he could denote the passage of time. But his enthusiasm for the

possibilities of his art went beyond a mastery of technique. Kurosawa, who

died in September of a stroke at the age of 88, saw film as a dynamic and

versatile language with which he could praise the forces of nature, decry the

evils of man, shed light on the problems of his country, and celebrate the

resilience of the spirit.

Dreams

Dreams Dreams

Dreams

He

was no more demanding on his cast and crew than he was on himself. In 1970,

after years of difficulty raising money for his projects, he made Dodes'kaden,

about the inhabitants of a Tokyo slum. The film, though one of his most

heartfelt, got tepid reviews and, for the first time in his career as a

director, lost money. The following year, despondent and suffering from a

chronic stomach ailment, he attempted suicide by slashing himself 22 times on

the arms, hands and neck. Discovered by his maid in a blood-filled bathtub, he

eventually recovered not only his health and spirits, but his career. In 1972 he

received an offer from the Soviet Union to write and direct anything he liked.

The resulting project, Dersu Uzala, took four years to complete, and won an

Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. He would make five more films before he

died. Among them, Ran (1985) and Dreams (1990) stand out as two of the most

visually arresting of all time.

He

was no more demanding on his cast and crew than he was on himself. In 1970,

after years of difficulty raising money for his projects, he made Dodes'kaden,

about the inhabitants of a Tokyo slum. The film, though one of his most

heartfelt, got tepid reviews and, for the first time in his career as a

director, lost money. The following year, despondent and suffering from a

chronic stomach ailment, he attempted suicide by slashing himself 22 times on

the arms, hands and neck. Discovered by his maid in a blood-filled bathtub, he

eventually recovered not only his health and spirits, but his career. In 1972 he

received an offer from the Soviet Union to write and direct anything he liked.

The resulting project, Dersu Uzala, took four years to complete, and won an

Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. He would make five more films before he

died. Among them, Ran (1985) and Dreams (1990) stand out as two of the most

visually arresting of all time.